Our community and other Afro-descendant tribal communities on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast are confronting what seems to be a systematic attempt by the state to uproot our community. For decades, Costa Rica has refused to grant property titles and infringed on our rights to property by targeting ownership over our ancestral lands, even to the extent of issuing demolition orders.

We are resisting. Our story of resilience begins in Nigeria, Gambia, Equatorial and Western regions in Africa, extending to the shores of the Caribbean Sea. In the lush tropical rainforest of Costa Rica, between the symphony of cicada singing and the dance of the jungle canopy, we have been autonomous on the shores of the Caribbean Sea for centuries. A past of struggle wove the tapestry of the rainforest and sea, giving rise to our deep connection with our ancestral lands.

I was born and raised in Old Harbor, where leaves whisper, waves tell tales, and the spirits of our Igbo ancestors softly speak. As a bearer of our collective memory of the Afro-Caribbean legacy, I share this rich narrative with my son, Omi, age six. Hand in hand, we tread the very shores our ancestors once walked, guided by stars, the Caribbean sea and stories, along the historical beach path that our people journeyed by foot and by horse, connecting the vibrant tapestry of the Creole communities of the coast in Central America.

“Omi,” I say, as we gaze across the vast sea, “your name means ‘water’ in Yoruba; this symbolizes the journey of our ancestors from Africa to the West Indies to these shores. It reflects our strength, our resilience.” As a mother and his first educator, I weave our oral history into our daily lives, ensuring that the legacy of our ancestors, their struggles and triumphs, are etched in his heart, for he, too, must live in this skin.

My great-grandfather, William Brown Duff, was a son of the Caribbean. Only one generation separated him from the shackles of enslavement; in his memories lived the terror his grandparents shared of their travails on their voyage to Jamaica from Nigeria and the subhuman fate they met there. William, just 12 years old at the time, embarked from Jamaica in search of a better life. He worked as a water carrier in constructing the Panama Canal, traveled through Nicaragua, and finally, in 1918, settled in Costa Rica with my great-grandmother, Viola Smith, belonging to the founding family of Cahuita. William entered this tropical coastal world unaware of the challenges this new environment would present: malaria, endemic to the rainforest, and the hostile climate constantly testing the resolve of its inhabitants, thus, the resilience and indomitable spirit of our Black community.

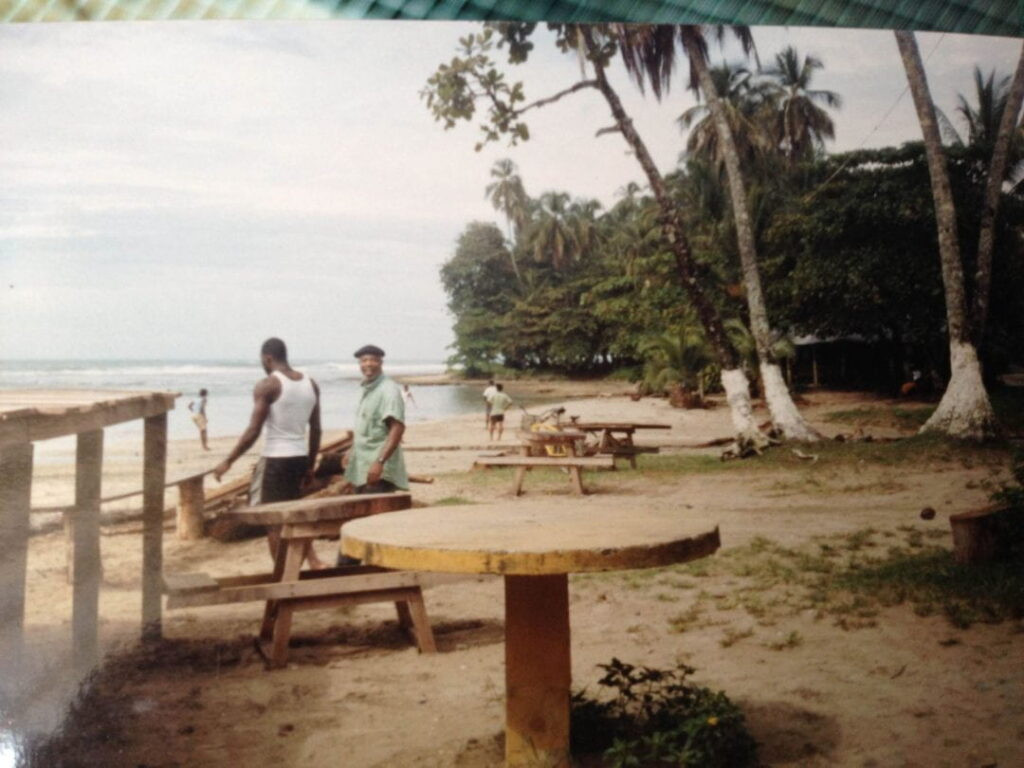

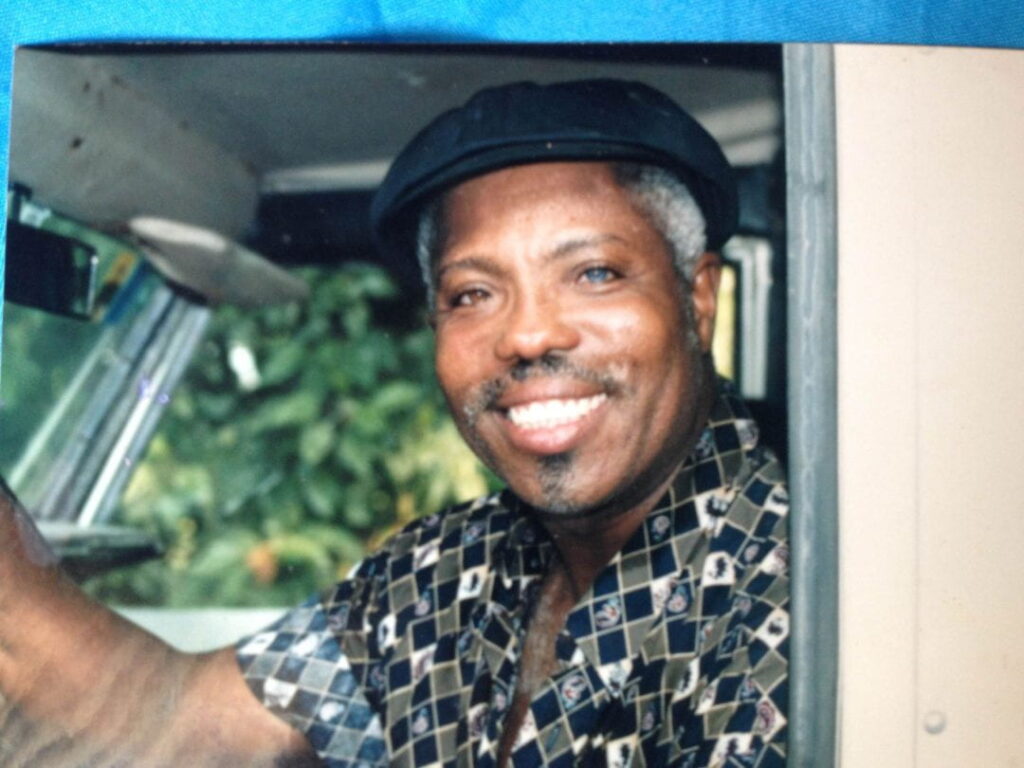

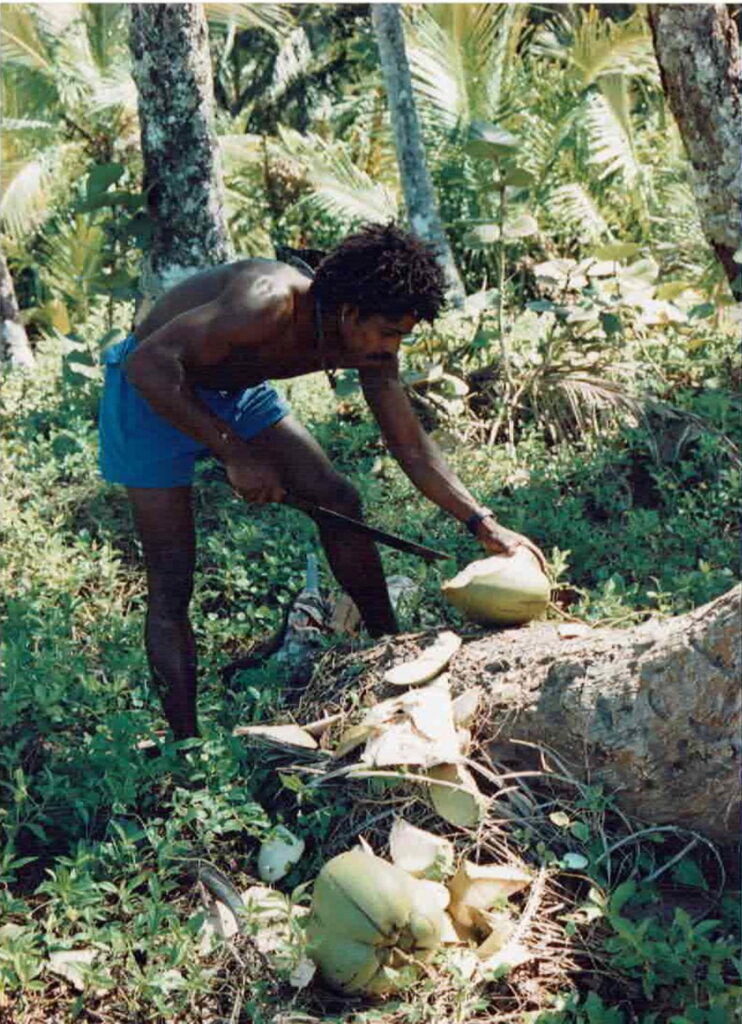

Our ancestors, the Bryants, Hudsons, Smiths, and many more of the founding families of Cahuita’s district, forged the towns of the southern Caribbean of Costa Rica with their work-rough hands and unbreakable spirits. As Omi and I tread the sandy shores, our steps lead us to the fertile grounds of Mr. Edgar Campbell’s farm. The air is filled with the rich scent of earth and growing herbs, spices, fruit trees and medicinal plants “Bush Medicine”, the land’s abundant vitality. Mr. Campbell, a man whose smile beams like the morning sun as he spots us. “Ah, visitors! Welcome, welcome!” He greets us warmly. We venture through his land to pick coconuts to quench our thirst, with a stride that spoke of deep familiarity and reverence for the land, guiding us through his farm, an expanse of rich soil and crops, a living narrative of resilience and heritage.

As we walked, the tranquility of the surroundings provided the perfect backdrop for Edgar to unfold the stories of why we created Afro cooperatives as agricultural ventures of cultural and environmental preservation. “The creation of Coopecacao Afro, as many more afro organizations and initiatives” Edgar began, his voice carrying the weight of the story he was about to tell, “was primarily a means to protect our land rights.”

He shared with us how, in the district of Cahuita, the land is more than a physical asset; it’s the soul of the community, entwined with centuries of history, culture, and ancestral wisdom. The cooperative emerged from a dire need to shield this heritage from the encroachments of external interests and to assert the community’s sovereignty over these ancestral lands. Edgar and fellow members in our community embarked on a journey to sustainably manage resources, leveraging agroecological practices that honor the earth and its cycles.

As we paused by a patch of cacao trees, Edgar plucked a ripe pod from the branches, splitting it open to reveal the rich, fresh beans inside. “These,” he said, gesturing towards the beans, “are more than the source of chocolate, they’re a symbol of our identity, of our struggle and resilience. By producing our chocolate, we’re creating a product; we’re reclaiming our heritage and ensuring the survival of our traditions for generations to come.”

Omi listened intently, his young eyes wide with the unfolding realization of the land’s deep stories. Edgar’s narrative is an account of agricultural practice and a lesson in stewardship, resistance, and the profound bond between people and their land.

As we continued our walk, the conversation shifted to the future—how Coopecacao Afro was cultivating opportunities for the youth, ensuring that children like Omi would grow up empowered by the knowledge of their land and the strength of their roots. Edgar’s vision was clear: a community self-sufficient and resilient, bound by the shared goal of preserving the cultural and environmental legacy.

Our journey through Edgar Campbell’s farm was a passage through the layers of history, struggle, and hope.. Edgar turned to Omi, his gaze both stern and warm. “Remember, young man,” he began, his voice firm yet imbued with an almost paternal kindness, “a Black man’s farm is his pantry.”

He paused, allowing the weight of his words to sink in, then continued, “It’s crucial for us to rely on ourselves, to nurture our community and our families with what the earth gifts us.” With a gesture that encompassed the expanse of his farm, he shared the essence of his wisdom, “Here, we grow more than just food; we cultivate life. From the crops that feed us to the medicinal herbs that heal us, like the ‘BUSH TEA’ make sure you drink ‘bear bush,’ every part of this land sustains us.” Edgar’s farewell to us included a quote by Marcus Mosaih Garvey, reminding us that “a people without knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots. ”As we left the farm, the setting sun casting golden light over the fields, I could see a new understanding reflected in Omi’s gaze. It was a recognition of the importance of roots, of land, and of the stories that bind us to both.

The Unseen Battle of Costa Rica’s Afro-Descendant Communities

In Costa Rica, a nation renowned for its dedication to peace and environmental conservation, lies a less visible narrative that contrasts sharply with its idyllic image. This narrative belongs to us, the Afro-descendant communities of the Caribbean coast, who find ourselves trapped in a struggle against laws that threaten our very existence on our ancestral grounds. Despite Costa Rica’s international acclaim for its lush rainforests and commitment to ecological preservation, our story reveals a different reality—one in which the principles of environmentalism justify the displacement of Afro-communities with deep-rooted historical and cultural ties to these lands.

The challenges of race and racism in Latin America and the Caribbean are complex and pervasive, and Costa Rica is no exception. Our territories—the lands our ancestors have nurtured, cultivated, in great harmony with nature and called home for generations—are under siege. This reality transcends national borders, languages and histories, uniting us with other Afro-descendant populations in a shared struggle for recognition and rights. Costa Rica’s approach to managing its environmental resources under the guise of conservation has led to the systematic uprooting of our communities. This sophisticated masquerade of ecological stewardship, which has garnered international praise, masks a bitter truth: the displacement of people under the pretext of protecting nature.

The irony of this situation is profound. As Costa Rica receives accolades for its environmental initiatives, the lands and traditions of Afro-Caribbean communities are quietly being eroded. Our rights, histories and very identities are swept away in the so-called tide of progress, leaving us to contend with the ramifications of policies that fail to acknowledge our existence and contributions to the cultural and ecological fabric of the nation. This scenario underscores the challenges and achievements concerning race and racism in Costa Rica, revealing a nation grappling with deep-seated issues of racial displacement and discrimination, all under the veneer of environmentalism.

A Legacy Overlooked and Under Threat

The Constitution of Costa Rica, with its amendments emphasizing a multiethnic and pluricultural society, promises equality, property rights and environmental protection. These legal frameworks were intended to herald a new era, recognizing the diverse tapestry of cultures that constitute the nation. However, the reality for Afro-descendant communities, particularly in regions like Limon, sharply contrasts with these constitutional promises. Despite legal recognition, we continue to navigate a landscape marred by systemic discrimination, exclusion and the looming threat of displacement—a stark reminder of the chasm between legal ideals and their implementation.

Nearly a decade since these constitutional amendments, the Afro-descendant communities of Costa Rica remain embroiled in a struggle for recognition, battling systemic barriers that hinder our access to justice, education and equitable treatment. The caribbean of Limon province has become a battleground for our rights.The principle of non-retroactivity, meant to protect acquired rights, and the promises of equality before the law seem to dissolve when faced with the realities of the district of Cahuita and other Afro-descendant settlements, our ancestral lands, are now under threat. They are classified under laws that render our claims and existence void. While noble in their intentions, environmental regulations and conservation efforts have been applied in ways that disproportionately affect our communities in negative ways. The creation of the Institute of Land and Colonization in 1961, an entity that enacted a massive program of land titling in the name of the state, disregarded the ancestral rights of our people, including public and private family cemeteries. The state has claimed ownership over our lands and even our ancestors’ remains, a move that ironically coincided with the time in which Blacks were given the right to vote and participate in government.

The Struggle Against “Ley sobre la Zona Marítimo Terrestre” 6043

The Maritime Zone Law (Law No. 6043) is a critical focal point because the legislation governing the coastal maritime zone threatens to displace our ancestral communities of African Descent. The law ostensibly aims to protect and manage the coast for the public good, emphasizing conservation and responsible development. However, the reality for our Afro-descendant communities, whose lives and livelihoods are intrinsically tied to these lands, tells a story of displacement and disenfranchisement, glossed over by the law’s environmental objectives.

Our ancestors, who have historically cultivated this land and relied on the sea for sustenance, find themselves at odds with a law that does not recognize their existence. The law declares the coastal maritime zone as inalienable and imprescriptible, effectively stripping us of any claim to these lands, regardless of how long we have inhabited them. It mandates that beachfront areas within the first 50 meters (164 feet) from the high tide line are designated as public space and the subsequent 150 meters (492 feet) as restricted are under state control, ousting the historical communities that have existed much before these laws.

Our practices of fishing, coconut cultivation and the utilization of bush remedies—traditions passed down through generations—are now under threat. The oversight responsibilities vested in the Costa Rican Tourism Institute and the direct compliance mandates for municipalities further complicate our struggle. While the law outlines a comprehensive framework for protecting and managing the coastal zones, it starkly fails to incorporate the rights and voices of the Afro-descendant communities. Our ancestral homes and businesses are marked for demolition, labeled as obstructions to the state’s environmental and developmental visions.

This legal situation is exacerbated by natural disasters, such as the earthquake that led to soil liquefaction in Limón province, further destabilizing our communities and bringing the coastline closer to our homes. The rise in the Costa Rican coastline by up to 6.2 feet facilitated the state’s justification for demolishing our homes and uprooting our communities, citing the need to reclaim the expanded maritime zone.

This law and its implementation embodies the broader challenges we face in securing our rights and preserving our heritage. Our fight against this legislation is not a stand against conservation, for we have always lived harmoniously with nature, but a call for a more inclusive, equitable approach that recognizes and respects the rights of all communities, especially those of African descent, who have been stewards of these lands long before their current designation as protected areas.

The “Ley sobre la Zona Marítimo Terrestre” represents a critical juncture in our ongoing struggle for recognition, justice and the right to live in harmony with the lands our ancestors have cultivated for centuries. It underscores the need for dialogue, for laws that protect the environment and uphold the rights and traditions of the communities that have coexisted with these natural spaces. Our plea is for a reevaluation of this legislation, for policies that acknowledge our historical presence, and for a future where our children can continue to thrive on the lands of their forebears, free from the threat of displacement and erasure.

Conservation’s Irony and the Impact on Afro-descendant Communities

The creation of Tortuguero National Park in the 1970s marked the beginning of a conservation era that, while crucial for the global fight against environmental degradation, inadvertently set the stage for the systematic displacement of our people. Nestled in the lush province of Limón, this park, a haven for biodiversity, became one of the first battlegrounds where the complex relationship between conservation objectives and community rights unfolded. The creation of the park and subsequent protected areas like the Barra del Colorado Wildlife Refuge not only highlighted the nation’s commitment to environmental preservation but also underscored a glaring oversight: the failure to adequately consider the impact of these initiatives on the Afro-descendant populations.

The expansion of conservation areas throughout the 1970s and 1990s, including the establishment of the Gandoca-Manzanillo Wildlife Refuge and the designation of Cahuita National Park, further complicated the lives of those within their boundaries. Our ancestral ties to these lands, predating the establishment of protected areas, were seemingly disregarded in favor of a broader conservation narrative. This dissonance between the goals of environmental preservation and the rights of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities to their ancestral lands highlights a critical gap in the conservation discourse. This gap overlooks the human dimension of environmental stewardship.

The conservation story in Costa Rica, particularly in the context of Afro-descendant communities, is a poignant reminder of the need for a more inclusive approach to environmental policy. It challenges us to reconsider the frameworks within which conservation efforts are conceptualized and implemented, urging a shift towards models that recognize and integrate local communities’ rights, knowledge, and practices. Our struggle for land rights and recognition within the framework of environmental conservation is not just a local issue but a microcosm of a global challenge: balancing the imperative of environmental protection with the rights and livelihoods of those who live in and around protected areas.

In this journey, we seek to protect our ancestral lands and redefine the conservation narrative to include the voices and wisdom of Afro-descendant communities. It is a call to acknowledge the symbiotic relationship between people and nature. It recognizes that faithful environmental stewardship requires an inclusive, equitable approach that honors the diversity of experiences, knowledge, and cultures that shape our world.

Cocles/Kekoldy

Another state-created conflict imposed upon our community began with the March 1976 creation of the Talamanca Indigenous Reserve and its subsequent boundary modifications two months later, all by executive decree. It included parts of the (ITCO)”Institute of Land and Colonization.” properties as an administrative annex to the Talamanca Indigenous Reserve, named initially the Cocles Indigenous Reserve. The delimitation of this annex was entrusted to ITCO and CONAI (National Commission for Indigenous Affairs).

A year and three months later, another executive decree expanded the reserve by about 5,700 acres with parts of other ITCO properties. However, inexplicably, it also included 3,074 acres that were not ITCO properties but predominantly lands owned by Afro-Caribbeans, located southeast of Cocles, along with about 1.4 miles of the maritime-terrestrial zone.

Five years later, the government acknowledged that the southeast part of the Cocles Indigenous Reserve had been occupied by non-Indigenous people for many years. As a result, a 1996 executive decree established that the 3,074 acres of non-Indigenous farms included in the previous decree’s delimitation were released.

As compensation for ITCO’s mistake, the Kekoldi Indigenous Reserve was expanded westward by a March 2001 executive decree, joining it with the Bribri Indigenous Reserve of Talamanca, forming a single geographical unit for the Bribri people, increasing the area of the Bribri Indigenous Reserve of Kekoldi (Cocles) to about 12,355 acres.

The Integral Development Association of the Bribri Indigenous Reserve of Këköldi (ADI-Kekoldi) sued the state, CONAI, and the Agrarian Development Institute (IDA) to recover the 3,074 acres of Afro and non-Indigenous farms. The judicial authorities restored the lands to those spelled out in the August 9, 1977, decree. It maintained the areas added as compensation, arbitrarily creating a conflict where none existed.

This decision has led to a land recovery process by the Indigenous people without compensation to the owners, including those in the maritime-terrestrial zone, affecting Afro-descendant properties and prompting conflict between two tribal peoples who previously coexisted in harmony.

The proposed solution is for INDER, in coordination with CONAI and ADI Kekoldi, to carry out the geographical delimitation of the territories comprising the Bribri Këköldi Indigenous Reserve as established by Decree in 2001, excluding properties belonging to Afro-descendants and non-Indigenous people. These boundaries should be ratified by law, as the limits set for Indigenous Territories cannot be altered to decrease their size except expressly by the law.

The Afro-tribal community acknowledges and appreciates the state’s recognition and territorial expansion granted to Indigenous peoples. However, such expansions should not come at the expense of another Afro-tribal community, mainly when the inclusion of their territories has resulted from inaccurate measurements acknowledged by the state. The state’s reliance on aerial surveys failed to recognize the longstanding presence of the Afro-descendant community, which has inhabited the area for centuries. The community emphasizes the importance of equal respect and protection of the ancestral rights of Afro-tribal communities; instead of issuing demolition orders and perpetuating the displacement of Afro-Caribbeans, we seek peaceful solutions that honor the historical and cultural significance of both communities, ensuring equitable treatment and fostering a spirit of mutual respect and coexistence.

Despite the international obligations of the Costa Rican state that prohibit it from instituting measures, whether policies, legal norms, or administrative practices, that deteriorate or worsen the situation of Afro-descendants, it has adopted a series of regressive measures such as officially repealing or suspending necessary legislation that allowed Afro-descendants to continue enjoying the rights recognized in those norms, such as the right to property titling, legal security and guarantees against evictions.

The Costa Rican state has enacted legislation and adopted policies that are manifestly incompatible with the existing national or international legal obligations regarding the rights recognized by Afro-descendants. To get really specific, for example, Law 6043 of 1977, Resolutions of the Constitutional Chamber (vote 3113-09 annuls law 8464, vote 2375-17 annuls law 9205), and Provisions of the Comptroller General’s Office (to the Ministry of Environment and Energy, report # DFOE-AE-IF-04-2011, and to the Municipality of Talamanca).

The Struggle for Recognition and Rights

The journey toward securing our rights and recognition has been long and arduous, marked by setbacks and milestones. Establishing the Afro-descendant Tribal Peoples Forum in Costa Rica represents a beacon of hope, an acknowledgment of our existence, and a platform for advocating our rights. This initiative, grounded in the principles of ILO Convention 169 and supported by the Presidential Decree on the Verification of Self-Recognition of Afro-descendant Tribal Peoples, marks a significant step forward in our quest for justice and self-determination.

Our engagement with national and international forums is not just about securing land rights; it’s about asserting our place in the world, advocating for our cultural preservation, and challenging the narratives that historically marginalized our communities. The struggle for recognition extends beyond the legal battles for land—it’s a fight for the preservation of our heritage, our language, and our traditions, which are inextricably linked to the land we call home.

The communities along the railroads that we built, and the communities of Barra del Colorado, Tortuguero, Guacimo, Siquirres, Matina, Limon, Cahuita, Puerto Viejo, Manzanillo and Sixaola, these communities predominantly of African descent have witnessed firsthand the deep-seated issues of systemic discrimination and segregation that have plagued our communities for generations. Our lands, rich in natural beauty and cultural heritage, are being stripped away by the state, a practice so normalized over the years that many of us started to accept it as inevitable. This isn’t just about losing parcels of land; it’s about the erosion of our identity and heritage.

The discrimination we face is pervasive, keeping us marginalized and silencing our voices in discussions about conservation, tourism, and national development. The railroad, which could have been a symbol of progress, instead reinforces our isolation and highlights the disparities we live with daily.

The struggle to protect our land and rights has been a relentless endeavor, passed down through generations before us. It looms over our present and, unfortunately, appears to be a looming challenge for future generations as well. We’re fighting against a system that seeks to displace and disempower us, challenging policies and practices that ignore our history and rights. It’s a struggle for the preservation of our way of life, our history, and our identity. True progress should uplift, not uproot, the communities it impacts.

Preserving Our Cultural Heritage: The Role of Education and Innovation

Our community has taken proactive steps to bridge the knowledge gap and empower our people through the Afro Costa Rica Information Initiative. By leveraging technology and innovation, we aim to enhance access to information, celebrate our rich cultural heritage and foster a sense of unity and pride among our community.

The Stanford Museum symbolizes our commitment to preserving our history and sharing our stories. More than a repository of artifacts, it is a space where our children can learn about the heroes of our past, the struggles we have overcome, and the rich tapestry of Afro-Caribbean culture that defines us. Through exhibits, workshops, and cultural events, the museum plays a crucial role in educating our community and visitors about the significance of our heritage and its preservation.

A Call to Action for Justice and Equity

As I reflect on the challenges we face and the strides we have made, I am reminded of the resilience that runs deep in our community. Our story is one of struggle but also one of hope and determination. We stand at a critical juncture in our history, where the decisions we make today will shape the future of our community for generations to come.

We call upon the Costa Rican government, international bodies and all stakeholders to recognize our rights, respect our heritage, and work with us to ensure a future where our community can thrive. As we continue to navigate the complexities of conservation, development and rights, let us remember that progress cannot be achieved at the expense of marginalized communities. We can only build a better future for all through inclusive, equitable and respectful approaches. Our journey is far from over, but with each step forward, we move closer to a world where justice, equity, and respect for all cultures and communities are not just ideals but realities.

Laylí Jeanette Tahiríh Brown Stangeland is a guardian and advocate of Afro-Caribbean heritage in Old Harbour, Cahuita, Costa Rica. Her work spans the cultural preservation of the Stanford Afro Museum and advocacy for the Afro Tribal communities’ rights in the southern Caribbean. As a businesswoman deeply connected to her roots, Laylí’s efforts highlight the resilience of Afro-Costa Rican culture. Connect with her journey through Instagram: caribecostarica, explore more at afrocostarica.com, or contact her at layli@afrocostarica.com.

Click the following button read the official article in ReVista – Harvard Review of Latin America